More Information

Submitted: December 04, 2025 | Accepted: December 11, 2025 | Published: December 12, 2025

Citation: Ouassas I, Younoussa FS, Rachid AB, Elhabti Y, Benaissi Y, Elamraoui F, et al. Clinical Manifestations and Diagnostic Challenges of Cytomegalovirus Infection in HIV Patients: A Case Series Study from Morocco. Int J Clin Virol. 2025; 9(2): 031-035. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.ijcv.1001067

DOI: 10.29328/journal.ijcv.1001067

Copyright license: © 2025 Ouassas I, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Cytomegalovirus; HIV; Opportunistic infections; Morocco; Real-Time PCR; Antiviral therapy

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnostic Challenges of Cytomegalovirus Infection in HIV Patients: A Case Series Study from Morocco

I Ouassas1#, F Saley Younoussa1#, Rachid Abi1*#, Y Elhabti1, Y Benaissi2, F Elamraoui2, S Elkochri1, MR Tagajdid1, H Elannaz1, S Hassine1, S Ouannass1, A Reggad2, M Elqatni2, Z Kasmi1, A Laraqui1, N Touil1, B Machichi1, K Ennibi2 and I Lahlou Amine1

1Virology Laboratory, Biomedical and Epidemiology Research Unit, Department of Virology, Mohammed V Military Teaching Hospital and Mohammed V University, Morocco

2Infectious and Tropical Diseases Department, Mohammed V Military Teaching Hospital and Mohammed V University, Morocco

#These authors are equally participated in the writing of this work

*Corresponding author: Rachid Abi, Virology Laboratory, Biomedical and Epidemiology Research Unit, Department of Virology, Mohammed V Military Teaching Hospital and Mohammed V University, Morocco, Email: [email protected]

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is a major cause of morbidity in immunocompromised patients, particularly those living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). This study describes the clinical manifestations, diagnostic approaches, and therapeutic challenges of CMV infection in HIV patients in Morocco. A descriptive retrospective study was conducted on seventeen (17) HIV patients with CMV infection, diagnosed by real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). Clinical, virological (HIV and CMV viral load, CD4 count), and therapeutic data were subsequently analysed. The mean age was 43 ± 10.7 years, with male predominance (94.1%). Digestive manifestations (29.4%) were the most frequent, followed by respiratory and neurological involvement (17.6% each). The mean CD4 count was 65.4 ± 56.2 cells/mm³. The mean CMV viral load was 2.39 ± 0.74 Log and the mean HIV viral load was 4.10 ± 1.55 Log. Antiviral therapy for CMV could not be initiated in 47% of patients due to its unavailability. The outcome was favorable in 88.2% of patients, with a mortality rate of 11.8%. In conclusion; CMV infection in HIV patients in Morocco occurs in the context of severe immunosuppression and presents with a varied clinical spectrum, dominated by digestive pathologies. Real-time PCR remains crucial for diagnosis. The unavailability of antiviral drugs constitutes a major challenge for management, highlighting the need to improve access to treatments in resource-limited settings.

Human cytomegalovirus (CMV), a member of the Herpesviridae family, is a ubiquitous virus transmitted through various body fluids and can be transmitted vertically during pregnancy. Primary infection is typically asymptomatic but can manifest as a mononucleosis-like syndrome. Exclusive to humans, CMV is primarily pathogenic in immunocompromised individuals (HIV patients, transplant recipients) and in the fetus in cases of maternal infection, where it can cause severe forms, whether from primary infection or reactivation [1,2].

In people living with HIV, especially when the CD4 count is < 100 cells/mm³, the risk of CMV disease is high [3], with manifestations ranging from transient febrile episodes to severe organ involvement [4].

The objective of this study is to report cases of CMV infection in patients living with HIV, to specify the diagnostic methods, and to identify the main obstacles to therapeutic management in our context.

This study was conducted at the virology center for infectious and tropical diseases of the Mohamed V Military Hospital. We performed a descriptive retrospective study based on a series of patients living with HIV who developed a CMV infection. Diagnosis and virological monitoring (HIV viral load, CD4 lymphocyte count, CMV viral load) were performed in the virology laboratory of our institution.

Data were extracted from medical records and supplemented by laboratory results, then analyzed using Excel software.

Inclusion criteria mandated complete medical records containing clinical data, HIV viral load, CD4 count, and virological results confirming CMV infection. Patients with incomplete records were excluded.

Given the unsuitability of serology for an immunocompromised population, the diagnostic approach relied exclusively on the direct detection of CMV DNA by real-time PCR. Viral DNA extraction was carried out using the Qiagen EZ1 automated system. Viral genome amplification was performed from plasma or, where clinically indicated, from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The CMV R-gene® (Altona Diagnostics, RealStar) kit was used for the detection and quantification of the viral load on the Rotor-Gene Q (Qiagen-cephed) thermocycler. The Quantification Standards contain standardized concentrations of CMV-speciic DNA. These Quantification Standards were calibrated against the 1st World Health Organization International Standard for CMV for Nucleic Acid Ampliication Techniques (NAT). The Quantification Standards can be used individually as positive controls, or together to generate a standard curve, which can be used to determine the concentration of CMV-specific DNA in a sample. Results were expressed in copies/mL and then converted to log to facilitate clinical interpretation and therapeutic monitoring.

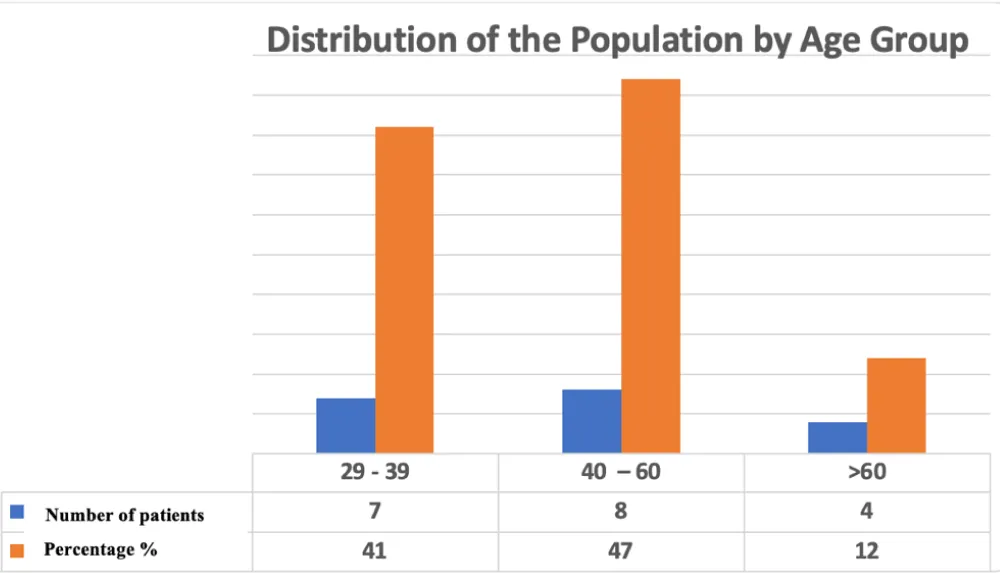

During the study period, seventeen (17) patients met the inclusion criteria. The mean age was 43 ± 10.7 years (range: 29-63 years), with a majority distribution in the 29-39 years (41%) and 40-60 years (47%) age groups. The population was predominantly male (16 men and 1 woman) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Age Distribution of the Study Population.

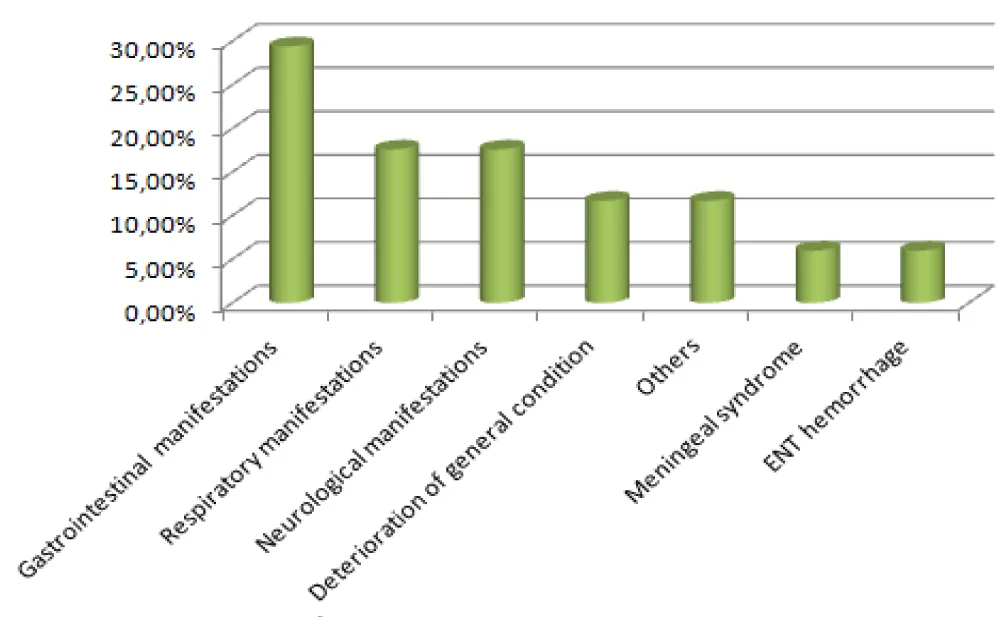

Reasons for hospitalization were varied, with a predominance of digestive manifestations (29.4%), followed by respiratory and neurological manifestations (17.6% each) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Patients According to Reason for Hospitalization.

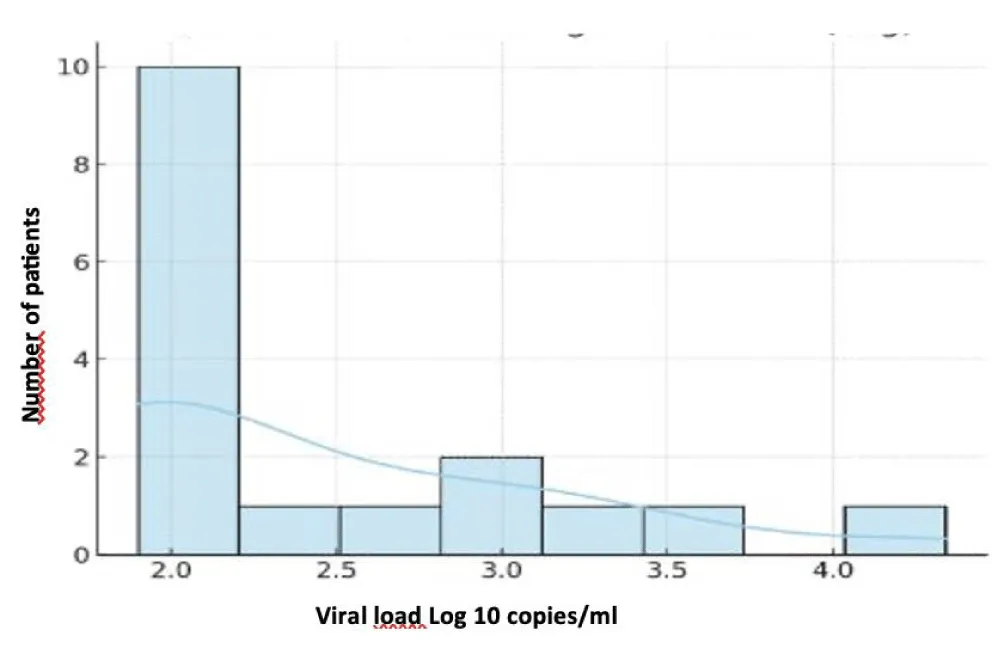

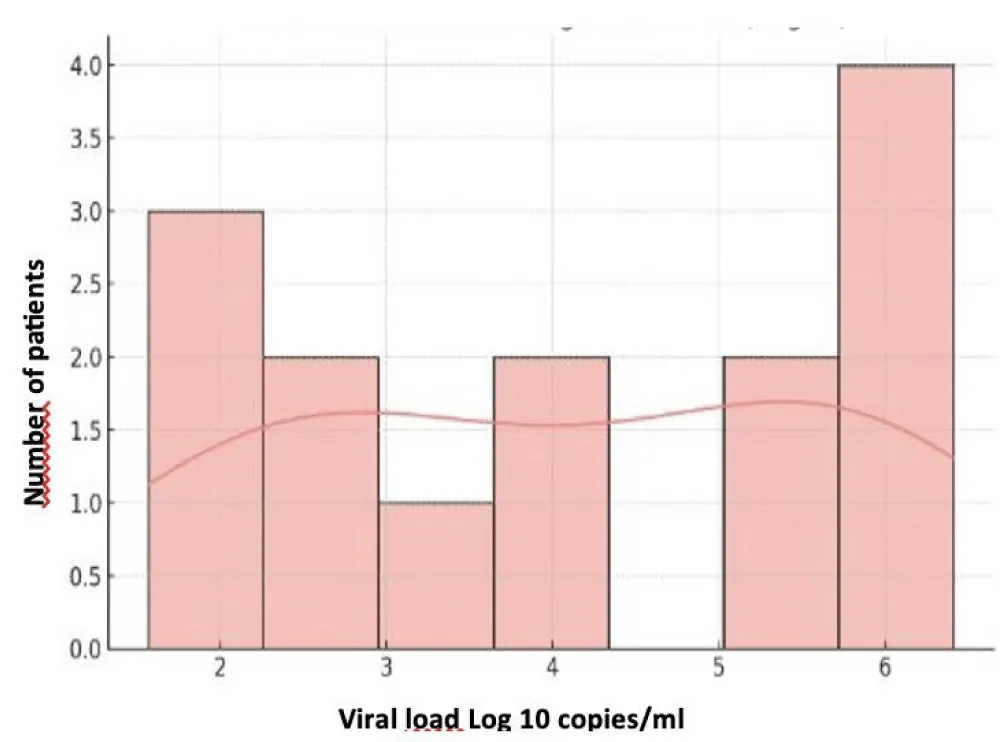

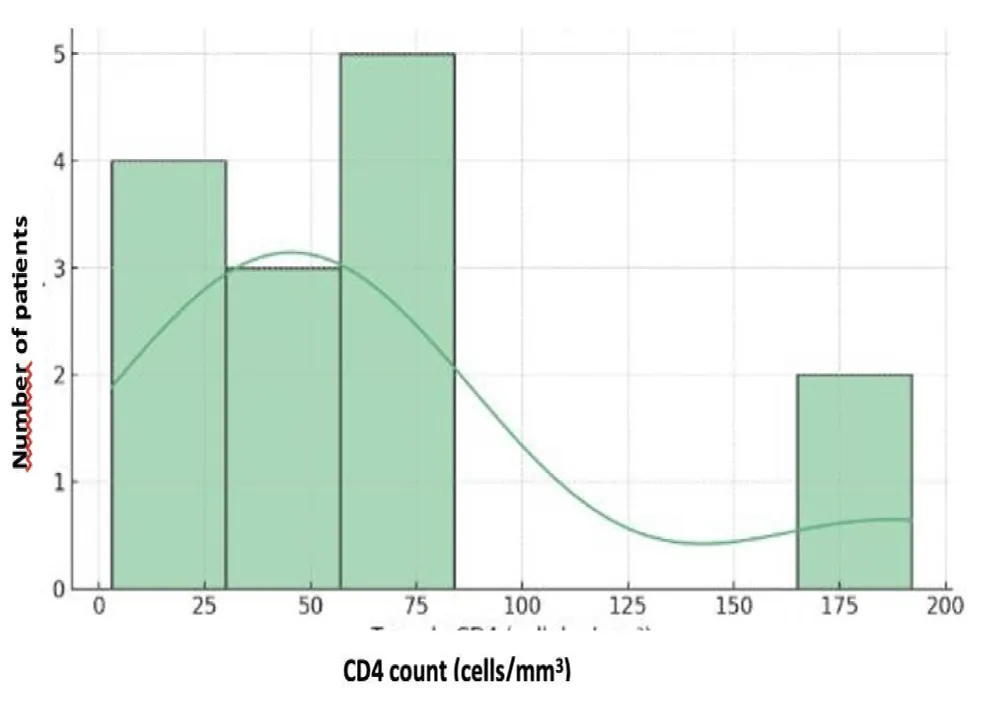

The mean blood CMV viral load was 2.39 ± 0.74 Log (min 1.90 – max 4.34 Log). CMV testing in the CSF, performed in two patients, was positive in one patient. The mean plasma HIV viral load was 4.10 ± 1.55 Log (min 1.57 – max 6.41 Log), with three patients having an unquantifiable viral load. CD4 T-lymphocyte counts ranged between 3 and 192 cells/mm³, with a mean of 65.4 ± 56.2 cells/mm³. The correlation between HIV and CD4 data is presented in Table VI (Figures 3-5).

Figure 3: Distribution of CMV Viral Load (Log10).

Figure 4: Distribution of HIV Viral Load (Log10).

Figure 5: Distribution of CD4 Lymphocyte Counts.

Antiviral treatment against CMV could not be initiated in 47% of cases due to its unavailability. The clinical outcome was favorable in 15 patients (88.2%), while 2 patients (11.8%) died.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) generally remains latent in immunocompetent individuals. In contrast, in immunocompromised patients, particularly those living with HIV, it can actively replicate and disseminate hematogenously, leading to CMV viremia and, in some cases, visceral involvement [5]. CMV infection thus represents one of the most frequently encountered opportunistic infections in this patient population. The incidence of CMV infections has decreased by 80% since the introduction of combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) [6].

Clinical manifestations occur mainly in patients with severe immunodeficiency, characterized by a CD4+ T-lymphocyte count below 100/mm³ [7]. In our series, the mean CD4 count was 65.4 cells/mm³, which clearly illustrates the link between severe immunosuppression and increased risk of CMV reactivation.

In HIV-infected patients, the clinical manifestations of CMV infection are varied and depend on the affected organ. Retinitis remains the most frequent complication reported in the literature, potentially leading to blindness [8]. In our study, digestive pathologies were the most frequent clinical manifestation (29.4% of cases), presenting as watery or mucous diarrhea, diffuse abdominal pain, and rectal bleeding. The colon was the most affected organ in the lower gastrointestinal tract, with colonic abnormalities ranging from mild colitis to deep ulcers observed during colonoscopy.

Respiratory involvement, observed in 17.6% of cases, included dry cough, dyspnea, purulent sputum, fever, and weight loss. Neurological involvement, also present in 17.6% of cases, manifested as tonic-clonic seizures, apyrexial consciousness disorders, gait disturbances, and memory impairments. Other observed clinical manifestations were asthenia (11.7%), cervical lymphadenopathy and kaposiform lesions (11.7%), meningeal syndrome with febrile headaches (6%), and minor ENT bleeding (epistaxis) (6%) [22].

The mean CMV viral load in our series was 2.39 ± 0.74 Log, with a maximum of 4.34 Log, while the mean HIV viral load was 4.10 ± 1.55 Log. These results underscore that high levels of viral replication coexist with severe immunosuppression, favoring the appearance of multiple and sometimes severe clinical manifestations.

CMV infections are endemic worldwide, with an estimated seroprevalence between 40% and 100%, higher in conditions of socioeconomic deprivation and lower in developed countries (approximately 50% by age 50) [9]. CMV co-infection is almost universal among people living with HIV [16]. Primary CMV infection triggers robust innate and adaptive immune responses and can manifest as a febrile mononucleosis-like syndrome but remains most often asymptomatic in immunocompetent individuals. Virus reactivation can lead to life-threatening complications in immunocompromised subjects [8,10].In advanced-stage HIV-infected patients, retinitis is the most frequent manifestation, accounting for about 85% of CMV-related complications, followed by gastrointestinal involvement (about 10%), neurological disorders, pneumonitis, hepatitis, and adrenal gland involvement [8]. The introduction of combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) in 1995-1996 significantly reduced the incidence of these conditions [11], but opportunistic CMV infection remains a major challenge in resource-limited areas, with a prevalence ranging from less than 5% to over 30% [12].

Contrary to literature data, which often report retinitis as predominant, our study found gastrointestinal involvement to be the most common manifestation [13], followed by respiratory and neurological pathologies. The observed gastrointestinal symptoms included diarrhea, abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, and fever, with colonic lesions ranging up to deep ulcers. Adrenal gland involvement, although rarely diagnosed clinically, has been reported in 84% of autopsies performed on HIV patients infected with CMV [14].

In immunocompromised patients, serology is unreliable for diagnosing active CMV infection. Antibody production is often delayed, both during primary infection and upon reactivation, and specific IgM may be absent [15,16]. Thus, serology cannot assess the severity of the infection, but it can help determine the immune status regarding CMV and guide prognosis.

The diagnosis of active CMV infection relies primarily on the direct detection of the virus. Real-time PCR is the method of choice for identifying viral DNA and quantifying the viral load, allowing for precise therapeutic monitoring [17,18]. In our study, PCR was performed on plasma for all patients and on CSF in two of them. Direct detection of the pp65 antigen in neutrophils is also used to confirm infection in immunocompromised patients but with operator-dependent sensitivity [16,21,22].

Cell culture allows for viral isolation and the performance of antiviral susceptibility testing, although it is slower and less sensitive [19,20]. It remains, however, the only method for obtaining strains to study viral resistance.

Treatment of the infection relies on antivirals active against CMV, mainly Ganciclovir and its prodrug Valganciclovir, Foscarnet, and Cidofovir [23]. Dosage adjustment is essential; underdosing can lead to therapeutic failure and the emergence of resistant strains, while overdosing increases the risk of toxicity [24,25]. Resistance, particularly to Ganciclovir, often results from mutations in the UL97 gene encoding the phosphotransferase.

The availability of antivirals is a crucial issue. In our study, nearly half of the patients could not receive treatment due to drug unavailability, which can compromise optimal management and worsen the prognosis [23].

Following our work, we work collaboratively with the hospital pharmacists to supply the reagents for PCR and the antiviral treatments necessary to be able to care for the patients.

In patients living with HIV, CMV co-infection is almost universal and remains a major cause of opportunistic infections, with retinitis being the most frequently reported complication. Early detection via sensitive and quantitative real-time PCR is essential to guide management.

The need for CMV treatment is increasingly observed in Morocco, especially with the rise in organ transplantation and cancer chemotherapy.

- Segondy M. Cytomégalovirus humain. In: EMC, Biologie clinique. Paris: Elsevier Masson SAS; 2009. p. 90-55-0035.

- Meyohas MC. Stratégies de prévention des infections à CMV chez les sujets immunodéprimés. Rev Fr Lab. 2002;(345):35-40. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0338-9898(02)80263-3

- Steininger C, Puchhammer-Stockl E, Popow-Kraupp T. Cytomegalovirus disease in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). J Clin Virol. 2006;37(1):1-9.Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2006.03.005

- Griffiths P, Baraniak I, Reeves M. The pathogenesis of human cytomegalovirus. J Pathol. 2015;235(2):288-97. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.4437

- Tagarro A, Del Valle R, Dominguez-Rodríguez S, et al. Growth patterns in children with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019;38(12):1230-5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/inf.0000000000002483

- Salmon-Ceron D. Manifestations cliniques de l'infection à cytomégalovirus au cours du SIDA. In: Nicolas JC, editor. Cytomégalovirus. Paris: Elsevier Collection MediBio; 2002. p. 121-9.

- Whitley RJ, Jacobson MA, Friedberg DN, Holland GN, Jabs DA, Dieterich DT, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of cytomegalovirus diseases in patients with AIDS in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: recommendations of an international panel. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(9):957-69. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.158.9.957

- Springer KL, Weinberg A. Cytomegalovirus infection in the era of HAART: fewer reactivations and more immunity. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54(3):582-6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkh396

- Imbert-Marcille BM. Histoire naturelle des infections à cytomégalovirus. Med Ther. 2001;7:577-84.

- Richman DD, Whitley RJ, Hayden FG, editors. Clinical Virology. 3rd ed. Washington (DC): ASM Press; 2009. p. 1408.

- Jabs DA. Cytomegalovirus retinitis and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-bench to bedside: LXVII Edward Jackson memorial lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151(2):212-41. Available from: https://www.ajo.com/article/S0002-9394(10)00817-2/pdf

- Ford N, Shubber Z, Saranchuk P, Pathai S, Durier N, O'Brien DP, et al. Burden of HIV-related cytomegalovirus retinitis in resource-limited settings: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(9):1351-61. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cit494

- Whitley RJ, Jacobson MA, Friedberg DN, Holland GN, Jabs DA, Dieterich DT, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of cytomegalovirus diseases in patients with AIDS in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: recommendations of an international panel. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(9):957-69. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.158.9.957

- Pulakhandam U, Dincsoy HP. Cytomegaloviral adrenalitis and adrenal insufficiency in AIDS. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;93(5):651-6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/93.5.651

- Dioverti MV, Razonable RR. Cytomegalovirus. Microbiol Spectr. 2016;4(2):10.1128/microbiolspec.DMIH2-0022-2015. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.dmih2-0022-2015

- Razonable RR, Paya CV, Smith TF. Role of the laboratory in diagnosis and management of cytomegalovirus infection in hematopoietic stem cell and solid-organ transplant recipients. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40(3):746-52. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.40.3.746-752.2002

- Sangavi SK, Abu-Elmagd K, Keightley MC, St George K, Lewandowski K, Boes SS, et al. Relationship of cytomegalovirus load assessed by real-time PCR to pp65 antigenemia in organ transplant recipients. J Clin Virol. 2008;42(4):335-42. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2008.03.031

- Larsson S, Söderberg-Naucler C, Wang FZ, Moller E. Cytomegalovirus DNA can be detected in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from all seropositive and most seronegative healthy blood donors over time. Transfusion. 1998;38(3):271-8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1537-2995.1998.38398222871.x

- Paya CV, Smith TF, Ludwig J, Hermans PE. Rapid shell vial culture and tissue histology compared with serology for the rapid diagnosis of cytomegalovirus infection in liver transplantation. Mayo Clin Proc. 1989;64(6):670-5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0025-6196(12)65346-4

- Paya CV, Holley KE, Wiesner RH, Balasubramaniam K, Smith TF, Espy MJ, et al. Early diagnosis of cytomegalovirus hepatitis in liver transplant recipients: role of immunostaining, DNA hybridization, and culture of hepatic tissue. Hepatology. 1990;12(1):119-26. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.1840120119

- Lautenschlager I, Halme L, Höckerstedt K, Krogerus L, Taskinen E. Cytomegalovirus infection of the liver transplant: virological, histological, immunological, and clinical observations. Transpl Infect Dis. 2006;8(1):21-30. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3062.2006.00122.x

- St George K, Rinaldo CR Jr. Comparison of cytomegalovirus antigenemia and culture assays in patients on and off antiviral therapy. J Med Virol. 1999;59(1):91-7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10440814

- Biron KK. Antiviral drugs for cytomegalovirus diseases. Antiviral Res. 2006;71(2-3):154-63. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.05.002

- Emery VC, Griffiths PD. Prediction of cytomegalovirus load and resistance patterns after antiviral chemotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(14):8039-44. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.140123497

- McGavin JK, Goa KL. Ganciclovir: an update of its use in the prevention of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in transplant recipients. Drugs. 2001;61(8):1153-83. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200161080-00016