More Information

Submitted: September 22, 2023 | Approved: September 29, 2023 | Published: October 02, 2023

How to cite this article: Bouteille S, Backaert W, Janssen K, Wollants E, Verbeek S, et al. Massive Adult Adenoviral Adenoiditis Mimicking Lymphoma. Int J Clin Virol. 2023; 7: 011-013.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.ijcv.1001054

Copyright License: © 2023 Bouteille S, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Adenoiditis; Adenovirus; Adenectomy

Massive Adult Adenoviral Adenoiditis Mimicking Lymphoma

Sandrine Bouteille1, Wout Backaert2, Kevin Janssen1, Elke Wollants3, Sanne Verbeek4, Griet Laureyns2 and Deborah Steensels1*

1Microbiology and Molecular Biology Department, Ziekenhuis Oost-Limburg, Genk, Belgium

2Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Ziekenhuis Oost-Limburg, Genk, Belgium

3KU Leuven, Rega Institute, Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Transplantation, Laboratory of Clinical and Epidemiological Virology, Leuven, Belgium

4Pathology Department, Ziekenhuis Oost-Limburg, Genk, Belgium

*Address for Correspondence: Deborah Steensels, Microbiology and Molecular Biology Department, Ziekenhuis Oost-Limburg, Genk, Belgium, Email: [email protected]

Hypertrophy of the adenoid is a rare condition in adults, often suspicious of malignancy. We present a case of a 31-year-old female with a clinical presentation of a giant nasopharyngeal mass, clinically suspicious for malignancy, given the size and greyish discoloration. She presented with left-side otalgia, hearing loss, and nasal obstruction. After broad investigations on adenoid tissue following adenectomy, a reassuring diagnosis of adenovirus-related adenoiditis could be made. This case demonstrates the importance of broad microbiological testing in ruling out malignancies. The patient recovered completely.

Nasal obstruction is a prevalent yet nonspecific symptom, present in a plethora of pathologies such as inflammation of the nasal mucosa or anatomical abnormalities such as nasal septal deviation [1]. Masses inside the nose can evidently also contribute to nasal obstruction. One example is (temporal or permanent) enlargement of the adenoid, blocking the nasal-nasopharyngeal passage. Moreover, an enlarged adenoid contributes to the development of Eustachian tube dysfunction and serous otitis [2]. Adenoid hypertrophy in adults is rarer and reminiscent of more severe entities like infection with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) or malignancy [3, 4].

We hereby present the case of a 31-year-old female with a strongly enlarged adenoid, clinically suspicious of lymphoma, which after broad testing returned to be adenoviral adenoiditis.

A 31-year-old, non-smoking female presented at the outpatient clinic of otorhinolaryngology with left-side otalgia and hearing loss. At that time, the general practitioner had already started treatment with 32 mg of methylprednisolone, amoxicillin 3 x 1000 mg/day, and a nasal spray containing dexamethasone and tramazoline for three days. Examination revealed serous otitis media and paracentesis was performed to drain fluid from the middle ear. The patient had a blank medical history, except for two miscarriages in the past.

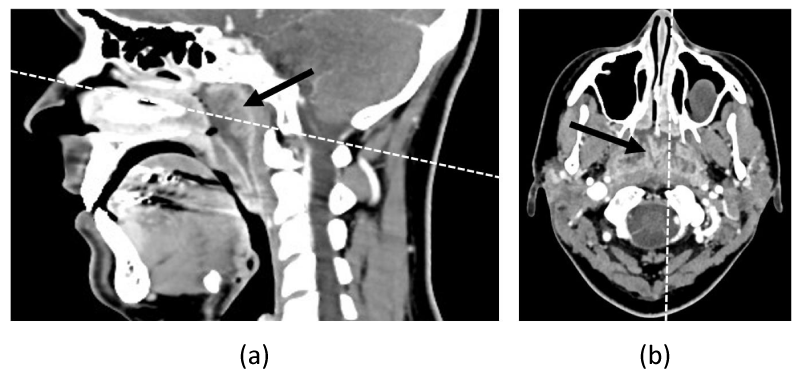

One week later, there was still hearing loss and additional nasal obstruction. There were no complaints of night sweats or weight loss. Otomicroscopy showed remaining serous otitis media, confirmed by tympanometry. Nasal endoscopy demonstrated congestion of the nasal mucosa, mucoid secretions, and a greyish mass in the nasopharynx. Blood analysis showed an increased white blood cell count (11.7 x 103/µL) and C-reactive protein (CRP) (105 mg/L). Given the suspicious aspect of the mass, an urgent Computed Tomography (CT) scan of the maxillofacial massive and neck was performed, which showed a substantial distension of the adenoid with enlarged lymph nodes in the neck (Figure 1).

Figure 1: (a) Sagittal and (b) axial CT images of maxillofacial massive show a contrast-capting nasopharyngeal mass. The dashed line in the sagittal image indicates the level of the axial image and vice versa. The mass is indicated with an arrow.

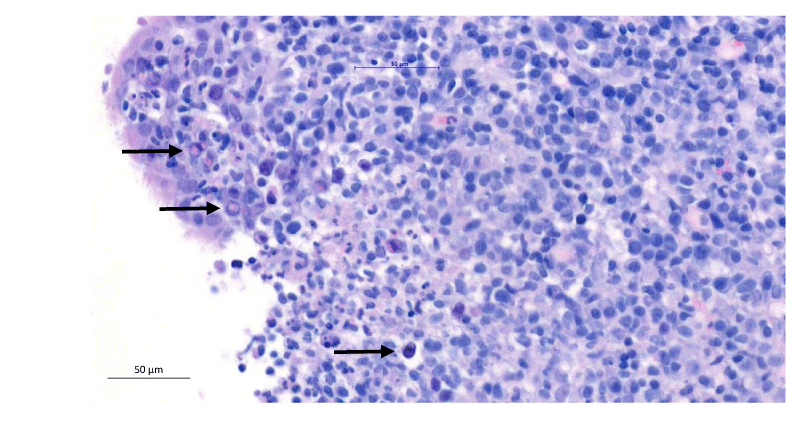

Due to the concern for a malignancy, a biopsy was taken under local anesthesia. Microscopic and immunohistochemical examination of the tissue showed the presence of ulcerative inflammation with the possible presence of viral inclusions (Figure 2). The presence of an underlying lymphoma could neither be confirmed nor excluded.

Figure 2: Microscopic image (hematoxylin-eosin staining) of the biopt. A selection of viral inclusions is indicated with an arrow.

Aerobic, anaerobic, mycobacterial, yeast, and mold cultures of the tissue showed no growth, and PCR for herpes simplex virus DNA was negative. The patient was seronegative for HIV, toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus, Borrelia burgdorferi, and Bartonella henselae. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen-IgG was found, excluding recent infection.

Follow-up was scheduled the following week for adenectomy and paracentesis under general anesthesia. During the surgery, the adenoid clinically seemed reduced compared with a week earlier. A nasopharyngeal swab, taken during the procedure, was negative for influenza A and B, SARS-coronavirus-2, coronavirus 229E, corona-virus HKU1, coronavirus NL63, coronavirus OC43, human metapneumovirus, rhino-virus/enterovirus, influenza A/H1, parainfluenza 1/2/3/4, Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), Bordetella pertussis, Chlamydia pneumoniae and Mycoplasma pneumoniae PCR (Biofire, FilmArray Respiratory Panel 2 plus). However, adenovirus PCR on the swab was positive with a weak viral load (cycle threshold (CT) 36) (RV Master assay, Seegene, Allplex RV-EA assay kit).

After surgery, the removed tissue was sent for pathological examination, bacterial culture, and PCR testing. Pathological examination demonstrated ulceration and active inflammation with reactive epithelial excitation and lymphoid hyperplasia based on histological, immunohistochemical, and molecular findings. Together with the previous week’s findings, it was concluded that there were no arguments for a malignancy. Bacterial culture showed growth of Haemophilus influenzae and anaerobic microbes, in the presence of other commensal flora of the oropharynx. Yeast-, mold- and mycobacterial cultures remained negative. Determination of herpes simplex and varicella-zoster virus DNA gave no new insights. Adenovirus PCR on the tissue was positive with a CT of 20.5, indicative of a very high viral load. The tissue was sent to the national reference center at University Hospital Leuven for further typing, which revealed the presence of adenovirus type 5 [5].

The patient recovered spontaneously during the following weeks. Nasal endoscopy three months later showed no residual signs of adenoiditis or adenoid hypertrophy.

A nasal endoscopy and CT scan of the sinuses suggested a mass in the nasopharynx. Since these examinations cannot distinguish malignant lesions from adenoid tissue, it is important to conduct a biopsy for further examination. Ultimately, it turned out to be hypertrophy of the adenoid caused by adenovirus type 5.

Due to its anatomical localization, an enlarged adenoid can cause nasal obstruction. When this exists in children for a long time, it can interfere with normal facial growth. Compression of the orifice of the Eustachian tube leads to middle ear ventilation problems, which can ultimately result in otitis media with effusion [6].

The adenoid, as part of Waldeyer’s ring, plays an important immunological role early in life. Dynamic growth is seen between the ages of 3 to 6 years when many antigens are encountered for the first time [6]. By the age of 6 years, the adenoid undergoes involution, making the occurrence of adenoid hypertrophy rare in adults. However, chronic infections and irritants can cause re-proliferation of the regressed adenoidal tissue [4].

Adenoid hypertrophy is hence less frequent in adults. Therefore, clinical visualization of an enlarged adenoid triggers the thought of a potential malignancy, especially when there is a greyish discoloration [7]. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma comprises about 2% of all head and neck squamous cell carcinomas and is most common in males. It is featured by a marked geographical variation, where the incidence in western Europe and the USA is only 0,5 - 2/100,000 while this is 25/100,000 in southern China, northern Africa, and Alaska [8]. The other most frequent malignancy is a non-Hodgkin or Hodgkin lymphoma [3]. While 94% of nasopharyngeal masses eventually return as non-malignant, clinical suspicion of malignancy yields an odds ratio of 135.7 for malignancy [8].

Given the size of the adenoid and greyish discoloration, we were therefore alarmed for potential malignancy in the presented case. Luckily profound viral testing brought relieving news.

The human adenoviruses are a family of DNA viruses and consist of more than 60 serotypes that can further be divided into seven species (A-G). Clinical manifestations are serotype-specific and range from upper and lower respiratory tract infections with symptoms of a common cold to gastrointestinal infections. Transmission is achieved via aerosolized droplets, fecal-orally, or contaminated surfaces. Adenovirus type 5 is classified into species C, known for causing upper respiratory disease or hepatitis [9]. Surveillance in the United States between 2014 and 2017 showed that 3.4% of reported adenovirus detections could be classified as type 5 [10]. This type is seen mainly in children and adolescents and is rather rare in adults. An adenovirus infection is usually mild and self-limiting but may have a more severe course in young children and immunocompromised patients [9].

This extraordinary case illustrates the potential of adenovirus type 5 to cause adult adenoiditis with marked enlargement of the adenoid. Due to the rarity of this condition, malignancy is often suspected, making it important to perform broad microbiological testing for differential diagnosis.

Ethical consideration

The case patient has provided written informed consent for publication.

- Osborn JL, Sacks R. Nasal obstruction. American Journal of Rhinology & Allergy. 2013; 27:15-16. https://doi.org/10.2500/ajra.2013.27.3889

- Mashat GD, Tran HH, Urgessa NA, Geethakumari P, Kampa P, Parchuri R, Bhandari R, Alnasser AR, Akram A, Kar S, Osman F, Hamid P. The Correlation Between Otitis Media with Effusion and Adenoid Hypertrophy Among Pediatric Patients: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2022 Nov 1;14(11):e30985. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30985. PMID: 36465218; PMCID: PMC9714957.

- Akhtar S, Khafaga Y, Edesa W, Al-Mubarak M, Rauf MS, Maghfoor I. Hodgkin lymphoma involving extranodal sites in head and neck: report of twenty-nine cases and review of three-hundred and fifty-seven cases. Hematology. 2021 Dec;26(1):103-110. doi: 10.1080/16078454.2020.1865667. PMID: 33478377.

- Rout MR, Mohanty D, Vijaylaxmi Y, Bobba K, Metta C. Adenoid Hypertrophy in Adults: A case Series. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013 Jul;65(3):269-74. doi: 10.1007/s12070-012-0549-y. Epub 2012 Mar 29. PMID: 24427580; PMCID: PMC3696153.

- Allard A, Albinsson B, Wadell G. Rapid typing of human adenoviruses by a general PCR combined with restriction endonuclease analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2001 Feb;39(2):498-505. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.2.498-505.2001. PMID: 11158096; PMCID: PMC87765.

- Niedzielski A, Chmielik LP, Mielnik-Niedzielska G, Kasprzyk A, Bogusławska J. Adenoid hypertrophy in children: a narrative review of pathogenesis and clinical relevance. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2023 Apr;7(1):e001710. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2022-001710. PMID: 37045541; PMCID: PMC10106074.

- Nicodemo J, Hamersley E, Baker P 3rd, Reed S. Benign adenoidal hypertrophy caused by adenovirus presenting as a nasopharyngeal mass concerning for malignancy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020 Nov;138:110300. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.110300. Epub 2020 Aug 8. PMID: 32823205.

- Abu-Ghanem S, Carmel NN, Horowitz G, Yehuda M, Leshno M, Abu-Ghanem Y, Fliss DM, Abergel A. Nasopharyngeal biopsy in adults: a large-scale study in a non endemic area. Rhinology. 2015 Jun;53(2):142-8. doi: 10.4193/Rhino14.130. PMID: 26030036.

- Khanal S, Ghimire P, Dhamoon AS. The Repertoire of Adenovirus in Human Disease: The Innocuous to the Deadly. Biomedicines. 2018 Mar 7;6(1):30. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines6010030. PMID: 29518985; PMCID: PMC5874687.

- Moro PL, Olson CK, Clark E, Marquez P, Strid P, Ellington S, Zhang B, Mba-Jonas A, Alimchandani M, Cragan J, Moore C. Post-authorization surveillance of adverse events following COVID-19 vaccines in pregnant persons in the vaccine adverse event reporting system (VAERS), December 2020 - October 2021. Vaccine. 2022 May 26;40(24):3389-3394. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.04.031. Epub 2022 Apr 12. PMID: 35489985; PMCID: PMC9001176.